The ultimate objective of a landscape approach is to support those that make a difference on the ground. This happens in many different ways, tailored to the specific needs and ambitions of each landscape. It would be wrong and inefficient to try and impose top-down or one-size-fits-all solutions. It would also undermine the definition I suggested in my previous blog – that a landscape is “a place with governance in place” – which implies that a landscape should be managed at the landscape level, by its stakeholders.

And at the same time we need a broadly accepted concept because landscapes do not exist in isolation. Lessons from landscape approaches must be possible to share, ideas need to be exchanged, progress communicated, investments drawn to the successful ones, and law enforcement alerted to the unacceptable ones. Not least, since we are also addressing key sustainable development issues nationally and globally, public opinion and policy circles must be made aware and made to recognize progress (as well as failure) on an aggregated level. In other words, we need a “common language” to describe what we want to achieve in landscapes and to determine whether progress is made.

Keep it simple, but not oversimplified

Political processes have often tried to establish such common languages through elaborate criteria and indicator systems. As I have discussed in earlier blogs here and here, these efforts can become quite complex and incomprehensible outside the initiated circles of the specific sector, and it is not easy to use these systems to determine progress. More importantly, when faced with a hundred expert-level indicators – how do you formulate policies that can be easily understood and supported by the wider public?

We see simplifications, perhaps most obviously when GDP is used as a sole measure of development in traditional macroeconomics. Similarly, the only widely accepted measure for forests is the forest area change (of which deforestation is one component). This is the one forest-related indicator applied in the Millennium Development Goals and deforestation appears to be by far the most visible forest feature in media. Another is the implicit success factor of farming – that is the amount of food produced, and related concerns when there are threats like climate change or droughts.

Clearly, economics, forestry and farming need relevant measures of progress: but it has been difficult to establish widely accepted frameworks that lie between the unnecessarily complex and the overly simplified.

Defining a framework and objectives

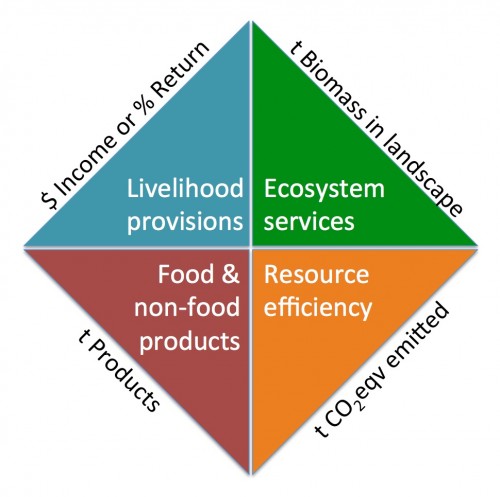

Over the past year, I have argued for a framework for landscapes with four generic objectives that can work across different kinds of landscapes – small and large, formal and informal. I think four is a reasonable number – it is easy to communicate and covers the multiple aspirations we must include. This is my list of landscape objectives:

1. Improved livelihoods

2. Sustained or improved ecosystem services

3. Sufficient delivery of food and non-food products

4. Efficient use of resources

Depending on the landscape in question, the relative weight on each of these objectives will vary, but all objectives would always be present, i.e. the weight would always be >0 for each objective. Moreover, while recognizing that there are a number of necessary means such as legal and institutional frameworks, land and resource tenure and rights, democratic processes, and gender equality that are not represented in the list, these four seem to cover the key ends fairly well.

Measuring progress towards the objectives

Now, to determine progress, we also need measures. This is where criteria and indicator systems often run into problems, because many different groups lobby for their own parameters and indicators . The current negotiation process towards Sustainable Development Goals is no exception. However, to ensure a common language, we need to fight for a small set of measures that can be used effectively to monitor, communicate, compare and support a learning process across landscapes. We also need measures that are scalable and easy to understand and acknowledged.

This requires some tough compromises and a lot of generosity from interested communities. As a starting point, I want to share the following proposal of one measure for each objective (see also Figure 1), noting that these are all well defined and relatively straightforward to measure, or at least estimate:

| Objective | Measure |

| Livelihoods | Income, or Return on capital (incl. distribution) |

| Ecosystem services | Total Carbon stock in the landscape |

| Food and non-food products | Amount, by product |

| Resource efficiency | Greenhouse gas emissions from the landscape |

Figure 1. Four possible generic landscape objectives with ideas on progress measures

Obviously, at the individual landscape level, a number of additional measures will have to be added to describe specific situations and ambitions. However, much can be gained by adopting a common set of measures, such as the above, that can be applied across all landscapes and form part of a common landscape language.

An important consideration is whether one should aim for absolute results (“we want to reach targets”) or if progress should be determined in relative terms (“we are moving in the right direction”). Personally, I favor a more relative way of determining progress, mainly because harmonized target-setting across landscapes is nearly impossible.

Having discussed the above with many colleagues, friends and others over the past year, there are some obvious omissions that would be good to have inside the generic set of measures. One is biodiversity and another is water supply, both of which can be seen as part of the ecosystem services objective. A third is pollution, beyond greenhouse gases, which can come under resource efficiency. The good news is that these can often be handled at a local level where the circumstances are better known and more specific. The bad news is that, to my knowledge, we have no general measures of these factors defined (yet) that can be applied globally and on all scales.

To conclude, this third landscape blog in my series means to suggest that it is possible to define a common language around objectives and also measures of progress for landscapes. The advantages of a common language can be significant. It will be possible to share experiences and scale up analyses and thereby the impact of landscape approaches.

With a common language, we can also benefit from shared methodologies for identifying and comparing options, as well as for decision-making processes and monitoring. Fortunately, there are many experiences in these areas. In my next blog I will build on them and share some thoughts on how the above framework could be used for analyses, decision-making and learning.

By Peter Holmgren, Director general, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)